I love watching my dog greet us when we come home after being out of the house for several hours. His body language displays a mix of running in circles, panting, bobbing his head up and down, wagging his tail vigorously, wagging his body vigorously, yapping, yipping, barking, doing the down-dog, shaking off, and finally, jumping into our laps. All of this activity is followed by a lot of of licking.

I love watching my dog greet us when we come home after being out of the house for several hours. His body language displays a mix of running in circles, panting, bobbing his head up and down, wagging his tail vigorously, wagging his body vigorously, yapping, yipping, barking, doing the down-dog, shaking off, and finally, jumping into our laps. All of this activity is followed by a lot of of licking.

There was a time not long ago when people routinely asked, “do animals have intelligence?” and “do animals have emotions?” People who are still asking whether animals have intelligence and emotions seriously need to go to a doctor to get their mirror neurons polished. We realize now that these are useless, pointless questions.

Deconstructing Intelligence

The change of heart about animal intelligence is not just because of results from animal research: it’s also due to a softening of the definition of intelligence. People now discuss artificial intelligence at the dinner table. We often hear ourselves saying things like “your computer wants you to change the filename”, or “self-driving cars in the future will have to be very intelligent”.

The change of heart about animal intelligence is not just because of results from animal research: it’s also due to a softening of the definition of intelligence. People now discuss artificial intelligence at the dinner table. We often hear ourselves saying things like “your computer wants you to change the filename”, or “self-driving cars in the future will have to be very intelligent”.

The concept of intelligence is working its way into so many non-human realms, both technological and animal. We talk about the “intelligence of nature”, the “wisdom of crowds”, and other attributions of intelligence that reside in places other than individual human skulls.

Can a Lizard Actually Be “Happy”?

I want to say a few things about emotions.

The problem with asking questions like “can a lizard be happy?” is in the dependency of words, like “happy”, “sad”, and jealous”. It is futile to try to fit a complex dynamic of brain chemistry, neural firing, and semiosis between interacting animals into a box with a label on it. Researchers doing work on animal and human emotion should avoid using words for emotions. Just the idea of trying to capture something as visceral, somatic, and, um…wordless as an emotion in a single word is counterproductive. Can you even claim that you are feeling one emotion at a time? No: emotions ebb and flow, they overlap, they are fluid – ephemeral. Like memory itself, as soon as you start to study your own emotions, they change.

And besides; words for emotions differ among languages. While English may be the official language of science, it does not mean that its words for emotions are more accurate.

Alas…since I’m using words to write this article (!) I have to eat my words. I guess I would have to give the following answer the question, “can a lizard be happy?”

Yes. Kind of.

The thing is: it’s not as easy to detect a happy lizard as it is to detect a happy dog. Let’s compare these animals:

HUMAN DOG COW BIRD LIZARD WORM

This list is roughly ordered by how similar the animal is to humans in terms of intelligent body language. Dogs share a great deal of the body language that we associate with emotions. Dogs are especially good at expressing shame. (Do cats feel less shame than dogs? They don’t appear to show it as much as dogs, but we shouldn’t immediately jump to conclusions because we can’t see it in terms of familiar body language signals).

On the surface, a cow may appear placid and relaxed…in that characteristic bovine way. But an experienced veterinarian or rancher can easily detect a stressed-out cow. As we move farther away from humans in this list of animals, the body language cues become harder and harder to detect. In the simpler animals, do we even know if these emotions exist at all? Again…that may be the wrong question to ask.

On the surface, a cow may appear placid and relaxed…in that characteristic bovine way. But an experienced veterinarian or rancher can easily detect a stressed-out cow. As we move farther away from humans in this list of animals, the body language cues become harder and harder to detect. In the simpler animals, do we even know if these emotions exist at all? Again…that may be the wrong question to ask.

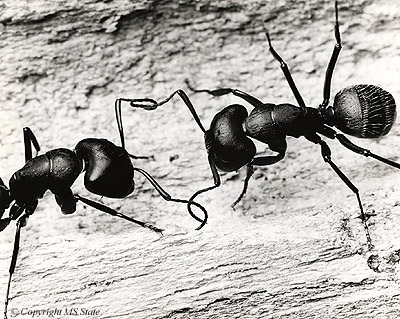

It would be wrong of me to assume that there are no emotional signals being generated by an insect, just because I can’t see them.

Ant body language is just not something I am familiar with. The more foreign the animal, the more difficult it is for us humans to attribute “intelligence” or “emotion” to it.

Zoosemiotics may help to disambiguate these problematic definitions, and place the gaze where it may be more productive.

I would conclude that we need to continue to remove those anthropocentric biases that have gotten in the way of science throughout our history.

When we have adequately removed those biases regarding intelligence and emotion, we may more easily see the rich signaling that goes on between all animals on this planet. We will begin to see more clearly a kind of super-intelligence that permeates the biosphere. Our paltry words will step aside to reveal a bigger vista.

When we have adequately removed those biases regarding intelligence and emotion, we may more easily see the rich signaling that goes on between all animals on this planet. We will begin to see more clearly a kind of super-intelligence that permeates the biosphere. Our paltry words will step aside to reveal a bigger vista.

I have never taken LSD or ayahuasca, but I’ve heard from those that have that they have seen this super-intelligence. Perhaps these chemicals are one way of removing that bias, and taking a peek at that which binds us with all of nature.

I have never taken LSD or ayahuasca, but I’ve heard from those that have that they have seen this super-intelligence. Perhaps these chemicals are one way of removing that bias, and taking a peek at that which binds us with all of nature.

But short of using chemicals….I guess some good unbiased science, an open mind, and a lot of compassion for our non-human friends can help us see farther – to see beyond our own body language.

For that matter, it is unlikely that an intelligent entity that can count could ever evolve on such a planet in the first place, because structure and differentiation at some physical level are required for living things to bootstrap themselves into existence.

For that matter, it is unlikely that an intelligent entity that can count could ever evolve on such a planet in the first place, because structure and differentiation at some physical level are required for living things to bootstrap themselves into existence.

Now consider aliens from a completely different kind of planet than Earth. What kind of math would originate in that world? Many people would argue that math is math and it doesn’t matter who or what discovers or articulates it. And there may be some truth to this. But we can only hope and imagine that this is the case.

Now consider aliens from a completely different kind of planet than Earth. What kind of math would originate in that world? Many people would argue that math is math and it doesn’t matter who or what discovers or articulates it. And there may be some truth to this. But we can only hope and imagine that this is the case.