(this blog post was originally published in https://eyemath.wordpress.com/ . It has been moved to this blog – with slight changes.)

Remember Nietzsche’s famous announcement, “God is dead“? In the domain of mathematics, Nietzsche’s announcement could just as well refer to infinity.

Remember Nietzsche’s famous announcement, “God is dead“? In the domain of mathematics, Nietzsche’s announcement could just as well refer to infinity.

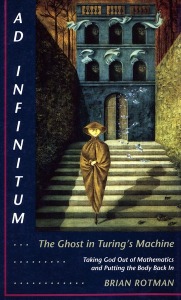

There are some philosophers who are putting up a major challenge to the Platonic stronghold on math: Brian Rotman, author of Ad Infinitum, is one of them. I am currently reading his book. I thought of waiting until I was finished with the book before writing this blog post, but I decided to go ahead and splurt out my thoughts.

————————

Charles Petzold gives a good review of Rotman’s book here.

Petzold says:

“We begin counting 1, 2, 3, and we can go on as long as we want.

That’s not true, of course. “We” simply cannot continue counting “as long as we want” because “We” (meaning “I” the author and “you” the reader) will someday die — probably in the middle of reciting a very long (but undoubtedly finite) number.

What the sentence really means is that some abstract ideal “somebody” can continue counting, but that’s not true either: Counting is a temporal process, and at some point everybody will be gone in a heat-dead universe. There will be no one left to count. Even long before that time, counting will be limited by the resources of the universe, which contains only a finite number of elementary particles and a finite amount of energy to increment from one integer to the next.”

Is Math a Human Activity or Eternal Truth?

Before continuing on to infinity (which is impossible of course), I want bring up a related topic that Rotman addresses: the nature of math itself. My thoughts at the moment are this:

You (reader) and I (writer) have brains that are almost identical as far as objects in the universe. We share common genes, language, and we are vehicles that carry human culture. We cannot think without language. “Language speaks man” – Heidegger.

Since we have not encountered any aliens, it is not possible for us to have an alien’s brain planted into our skulls so that we can experience what “logic”, “reality” or “mathematical truth” feels like to that alien (yes, I used the word, “feel”). Indeed, that alien brain might harbor the same concept as our brains do that 2+2=4….but it might not. In fact, who is to say that the notion of “adding” means anything to the alien? Or the concepts of “equality”? And who is to say that the alien uses language by putting symbols together into a one-dimensional string?

More to the point: would that alien brain have the same concept of infinity as our brains?

It is quite possible that we can never know the answers to these questions because we cannot leave our brains, we can not escape the structure of our langage, which defines our process of thinking. We cannot see “our” math from outside the box. That is why we cannot believe in any other math.

So, to answer the question: “Is math a human activity or eternal truth?” – I don’t know. Neither do you. No one can know the answer, unless or until we encounter a non-human intelligence that either speaks an identical mathematical truth – or doesn’t.

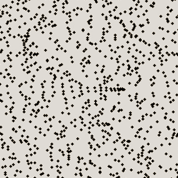

Big Numbers are Patterns

My book, Divisor Drips and Square Root Waves, explores the notion of really large numbers as characterized by pattern rather than size (the size of the number referring to where it sits in the countable ordering of other numbers on the 1D number line). In this book, I explore the patterns of the neighborhoods of large numbers in terms of their divisors.

My book, Divisor Drips and Square Root Waves, explores the notion of really large numbers as characterized by pattern rather than size (the size of the number referring to where it sits in the countable ordering of other numbers on the 1D number line). In this book, I explore the patterns of the neighborhoods of large numbers in terms of their divisors.

This is a decidedly visual/spatial attitude of number, whereby number-theoretical ideas emerge from the contemplation of the spatial patterning.

The number:

80658175170943878571660636856403766975289505440883277824000000000000

doesn’t seem to have much meaning. But when you consider that it is the number of ways in which you can arrange a single deck of cards, it suddenly has a short expression. In fact it can be expressed simply as 52 factorial, or “52!”.

So, by expressing this number with only three symbols: “5”, “2”, and “!”, we have a way to think about this really big-ass number in an elegant, meaningful way.

We are still a LONG way from infinity.

Now, one argument in favor of infinity goes like this: you can always add 1 to any number. So, you could add 1 to 52! making it 80658175170943878571660636856403766975289505440883277824000000000001.

Indeed, you can add 1 to the estimated number of atoms in the universe to generate the number 1080 + 1. But the countability of that number is still in question. Sure you can always add 1 to a number, but can you add enough 1’s to 1080 to each 10800?

Are we getting closer to infinity? No my dear. Long way to go.

Long way to “go”? What does “go” mean?

![]() Bigger numbers require more exponents (or whatever notational schemes are used to express bigness with few symbols – Rotman refers to hyper-exponents, and hyper-hyper-exponents, and further symbolic manipulations that become increasingly hard to think about or use).

Bigger numbers require more exponents (or whatever notational schemes are used to express bigness with few symbols – Rotman refers to hyper-exponents, and hyper-hyper-exponents, and further symbolic manipulations that become increasingly hard to think about or use).

These contraptions are looking less and less like everyday numbers. In building such contraptions in hopes to approach some vantage point to sniff infinity, one finds a dissipative effect – the landscape becomes ever more choppy.

No surprise: infinity is not a number.

Infinity is an idea. Really really big numbers – beyond Rotman’s “realizable” limit – are not countable or cognizable. The bigger the number, the less number-like it is. There’s no absolute cut-off point. There is just a gradual dissipation of realizability, countability, and utility.

Where Mathematics Comes From

Rotman suggests taking God out out mathematics and putting the body back in. The body (and the brain and mind that emerged from it) constitute the origins of math. While math requires abstractions, there can be no abstraction without some concrete embodiment that provides the origin of that abstraction. Math did not come from “out there”.

That is the challenge that some thinkers, such as Rotman, are proposing. People trained in mathematics, and especially people who do a lot of math, are guaranteed to have a hard time with this. Platonic truth is built in to their belief structure. The more math they do, the more they believe that mathematical truth is discovered, not generated.

I am sympathetic to this mindset. The more relationships that I find in mathematics, the harder it is to believe that I am just making it up. And for that reason, I personally have a softer version of this belief: Math did not emerge from human brains only. Human brains evolved in Earth’s biosphere – which is already an information-dense ecosystem, where the concept of number – and some fundamental primitive math concepts – had already emerged. This is explained in my article:

The Evolution of Mathematics on Planet Earth

I have some sympathy with Roger Penrose: when I explore the Mandelbrot Set, I have to ask myself, “who the hell made this thing!” Certainly no mathematician!

After all, the Mandelbrot Set has an infinite amount of fractal detail.

But then again, no human (or alien) will ever experience this infinity.

A key property of body language is that it is almost always unconscious to both giver and receiver.

A key property of body language is that it is almost always unconscious to both giver and receiver.

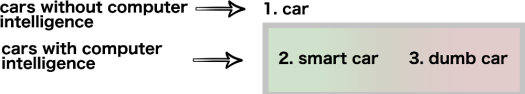

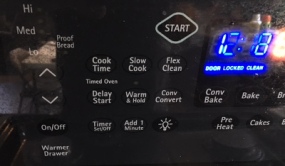

An old-fashioned industrial-age car comes with natural affordances: communication happens simply as a result of the physical nature of knobs, wheels, wires, engine sounds, torques, and forces. There are many sensory stimuli that the driver sees, feels, hears and smells – and often they are unconscious to the driver – or just above the level of consciousness.

An old-fashioned industrial-age car comes with natural affordances: communication happens simply as a result of the physical nature of knobs, wheels, wires, engine sounds, torques, and forces. There are many sensory stimuli that the driver sees, feels, hears and smells – and often they are unconscious to the driver – or just above the level of consciousness.

My first experience with a Prius was not pleasant. Now, I am not expecting many of you to agree with my criticism, and I know that there are many happy Prius owners, who claim that you can just ignore the geeky stuff if you don’t like it.

My first experience with a Prius was not pleasant. Now, I am not expecting many of you to agree with my criticism, and I know that there are many happy Prius owners, who claim that you can just ignore the geeky stuff if you don’t like it.