Consciousness is an emergent property of evolution. Like all things that resulted from evolution, we can gather evidence to come up with theories and explanations.

We should avoid (or postpone) the problem of subjective experience (qualia); we should intentionally remove the question of personal experience and switch to scientifically observable evidence.

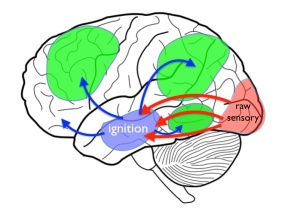

This idea was proposed by Stanislas Dehaene, in his book Consciousness and the Brain.

(image from http://www.brainfacts.org/neuroscience-in-society/supporting-research/2014/book-review-consciousness-and-the-brain)

A variation/interpretation of this idea is to redefine consciousness to be a property of living things or complex adaptive systems in general where certain common behaviors are exhibited. In the case of a wildcat hunting a rodent, with the implications of recognition, focus, attention, and other factors, we might be able to collect a set of markers of this kind of consciousness. There would not be a single marker, and we would not expect these markers to be consistent in all species, because consciousness could come in varying degrees, kinds, and loci.

In terms of degree, a snake probably has “less consciousness” than a fox. And a fox probably has “less consciousness” than a human. And all of these animals have “more consciousness” than a carrot.

But it may not be a matter of degree – perhaps it is more a matter of kind. (Is it possible to map raccoon-like consciousness to dolphin-like consciousness?)

Or it could be more a matter of locus (if there is anything like consciousness among ants – can it be found in a single ant’s brain? Or is it more likely to be distributed among a swarm of ants?)

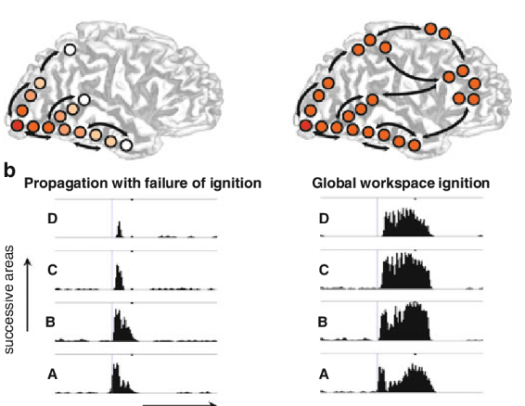

Brain imaging has become a powerful tool for using evidence-based science to get at the problem.

(image from https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/x4n4jcoDP7xh5LWLq/book-summary-consciousness-and-the-brain)

There’s an old gem of wisdom: if a Big Question defies the Big Answer, you might need to change the Question. Consciousness may need to be unshackled from subjectivity in order to be redefined using scientific evidence. As a consequence, there may be new and better ways to understand subjective experience.

Our subjective experience causes us to resist the act of defining consciousness based on evidence, because subjective experience is precious and tied to the self, which wants to be immortal.

When the answer to the Big Question comes, it might have two possible effects: (1) It might be unsavory and counterintuitive – similar to the way quantum physics is counterintuitive – but nonetheless indisputable and scientifically verified; or (2) It might unleash an orchestra of language, mental tools, metaphors, and intuitions, forming a major advance in human knowledge and understanding – not unlike the theory of natural selection itself.

Now, to be sure, I wasn’t expecting epiphanies to come tumbling out. After all, Richard Feynman famously said, “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.”

Now, to be sure, I wasn’t expecting epiphanies to come tumbling out. After all, Richard Feynman famously said, “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.”